Mouna Mounayer

(The following is adapted from a presentation I gave as a guest speaker at the Lebanese American University–on the 14th of April 2022–for an annual event honouring Lebanese poet Jawdat Haydar)

Today, for the most part, the muse is out of fashion, relegated to the attic of literature. At least that’s what I thought until I started writing fiction. People often ask artists where they get their ideas and inspiration. And from my own experience, I would have to say that inspiration comes in as many forms as there are people and ideas. A muse, therefore, is any source of inspiration you rely on to fuel your creativity and generate new ideas.

When I began my career as a documentary filmmaker, I didn’t believe in the concept of a muse, nor required it to make my films. Today, however, I’m writing fiction, and, for the first time, I have come to appreciate the unique bond that exists between artist and muse and what a muse can do for a creator in any medium.

By instilling the gift of lyrical expression in the simple writer, muses are designed to embrace the entire realm of creative writing, defined by the polar limits of fiction and truth, past and future. They are meant to inspire and enthuse. The fabled Heliconian Muses told the ancient Greek poet, Hesiod, that they could ‘utter many a fiction, and make it seem the truth.’ My muse is perhaps not the romantic ideal of the ancients, those Greeks and Romans who personified the poet’s creative power as seductive nymphs, with each of the nine members of the inspirational sisterhood presiding over a separate literary genre. The muses were known to these ancient storytellers as either Rememberers or Maddeners. ‘Madness,’ observed Socrates, ‘is necessary for one who approaches the Muses.’ Plato, on the other hand, personified the muses as that maddening impulse that drives men to exalted utterance. I wouldn’t go quite that far, especially when it comes to my own fiction, but who am I to argue with Plato?

Finding my muse was a challenge. I donned and discarded several famous Lebanese poets before I settled on Jawdat Haydar. I began with the ones I was most familiar with, like Nizar Qabbani, Gibran Khalil Gibran, and Amin Maalouf, to name a few, and though beautiful and inspirational in their own way, they didn’t rouse me to creativity. They each had something that I was looking for but none embodied the breadth of Lebanon’s human, political, and environmental conditions and modernity that I was looking for. I found their prose and/or poetry too limiting or too allegorical.

My novel, set in Mount Lebanon, is about a biracial archaeologist, an outsider, sucked into a situation she appears to have no control over, namely murder, and must contend with back-stabbing villagers, corrupt cops, and a sophisticated network of antiquities traffickers while proving her innocence, finding her place in society and winning the man she loves (a tall order, I know, but she’s up to it). One of the underlying themes I want to explore is Lebanon as a dream and a dream breaker. And it was with this theme that I finally found my muse, the Lebanese poet Jawdat Haydar. His strong, clear voice paints Lebanon in its true colours, sometimes sublime, sometimes gritty, but mostly as a country that can do better. Should do better. Lebanon, for Haydar, is a place steeped in history but forever poised on the precipice of potential.

In his poetry, Jawdat Haydar examines the heritage of his people, their history and environment and their fate, but the most interesting aspect about Haydar, for me, is the applicability of his poetry. JRR Tolkien once said that many confuse applicability with allegory, but the one resides in the freedom of the reader, and the other in the purposed domination of the author. This I discovered to be true of Haydar’s poetry. For the most part, he allows his readers the freedom to apply his poetry to anything in that reader’s life, regardless of the subject matter. I found that what he wrote about one issue could readily apply to another.

Never Scratch Nature

By Jawdat Haydar

We chariot to school to learn to read and write

Not to skin nature and rise to the sky

Not to work for fame by using dyn’mite

Pollute the world and by pollution die.

Folks awake and be aware of the reek

The death like hills of the chemical lees

Quick shut the flood gates of poison and seek

To stop being charioted to hades

Never scratch nature to bleed and react

For the falling blood is nothing but bane

Tis not a vision fancied but fact

Since we’ve polluted the air and the main

Why not be a hand in glove with nature

To ‘ve a serene and happy future

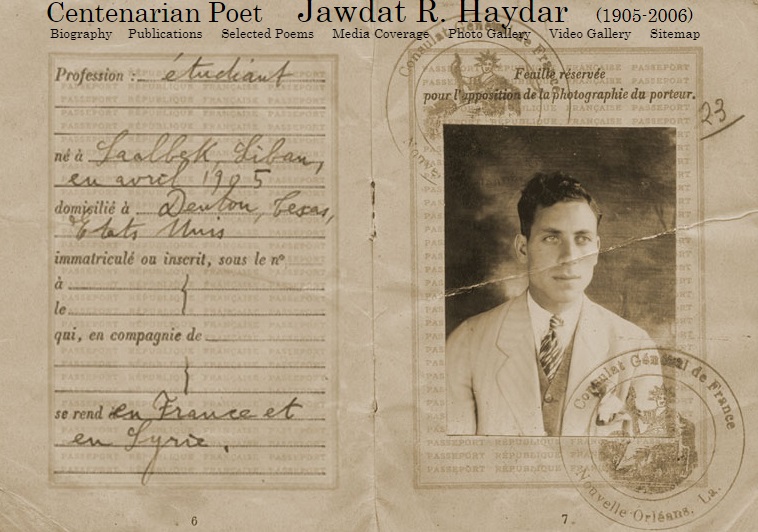

In his poem, Orpheus, Haydar wrote, “Orpheus pull out the strings of my heart and stretch them head to bottom on your lyre; Tighten them, tune them and please quickly start / The yearning melodies of my desire.” And that is exactly what I want, but unlike the mythical, forever youthful, Orpheus, my muse was 101 when he died in 2006. A Lebanese poet whose verse contains a deep sense of applicability and whose use of the English language is original, multi-layered, and adept at conveying feelings, images, and ideas of great complexity. Since I discovered him, Jawdat Haydar has inspired me to look deep beneath the surface and strive to find the precise words and tone with which to turn fiction into truth. Simply put, he is making me a better writer.

If you’re a writer, filmmaker or artist with a muse or looking for a muse, I would love to hear about your journey in the comments.

LAU: Paying Tribute to one of Lebanon’s greats, LINK: https://news.lau.edu.lb/2022/paying-tribute-to-one-of-lebanons-greats-jawdat-haydar.php

A beautiful blog post.

LikeLiked by 1 person